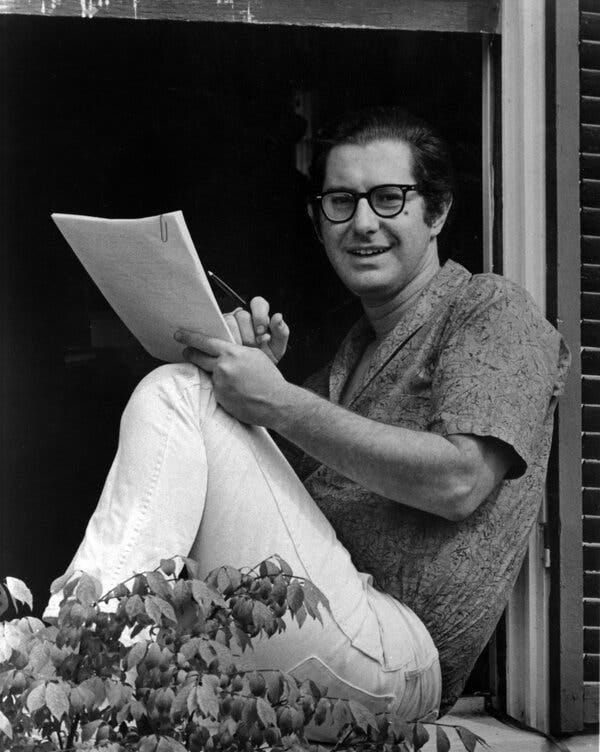

Over the past few years I’ve been, at first by seeming chance and lately by studied choice, encountering the works of the prolific poet, novelist, and translator David R. Slavitt. Time and again, I’ve found a generous universality in his translations and essays, and I wanted to take some time to appreciate him in gratitude for what his works have provided to me.

Born in a Jewish family, educated in the New England classical tradition, he was a much published author of broad tastes and interests, including some I would not care to touch (such as his erotic novels). He published well over 100 books, both original works and translations in the course of his life time, and I suppose must have had at least some notoriety, though his fame never reached my ears.

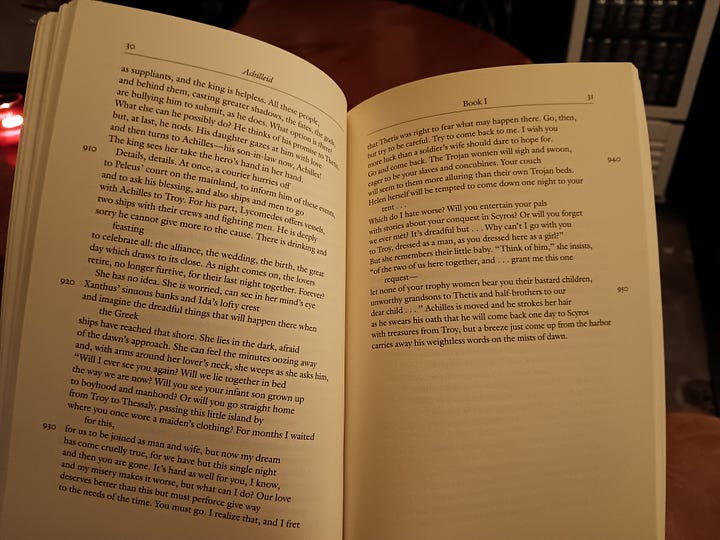

He had a particular love for Latin and Greek classics, and was quite the polyglot. I have mentioned his taste was broad; he translated 16th century French poetry, Armenia heroic stories, Latin epics and tragedies, Greek drama, and so on.

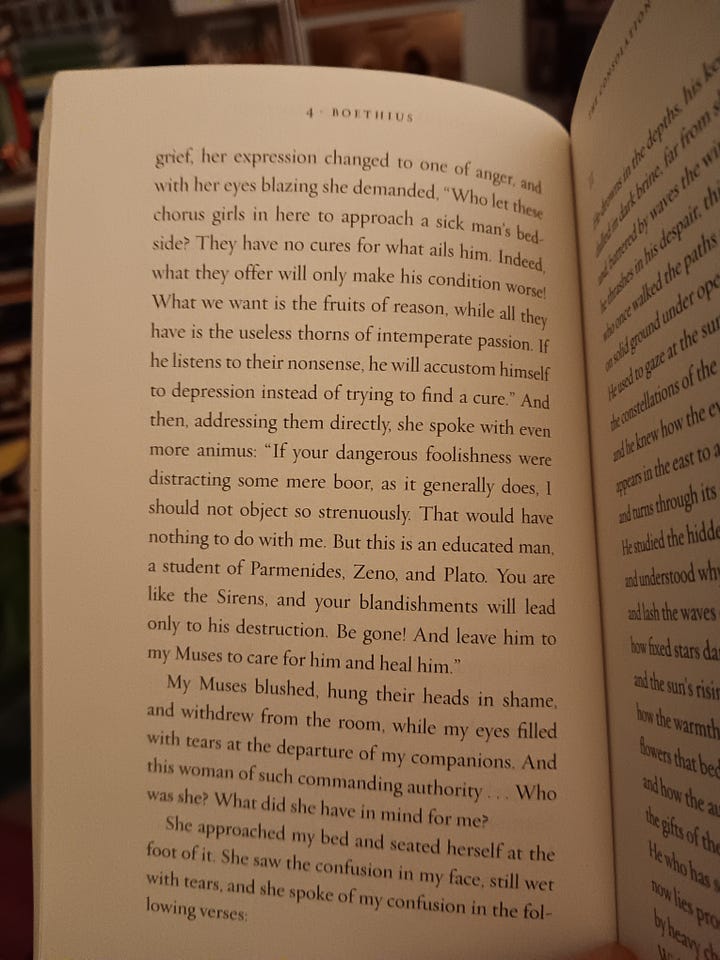

I first encountered him in his translation of Boethius’ Consolation of Philosophy. His introduction greatly informed and intrigued me, as he advanced both scholarly opinions with much nuance as well as a very sincere love of his subject matter and an advocacy for his continued relevance. This advocacy, especially for often overlooked or ignored works and authors is indeed something of a defining feature of the works of his which I’ve read. Continuing on to the translation, I was delighted to find the style easy and beautiful, and the poetry especially was translated in such a way that something of the beauty of the original Latin was transferred and passed on to me as reader. Indeed, he quite convinced me, by his introduction and the easy going, contemporary, yet elevated style which employed, to become exceedingly fond of Boethius, such that I now return to the Consolation when I’m lost in low spirits.

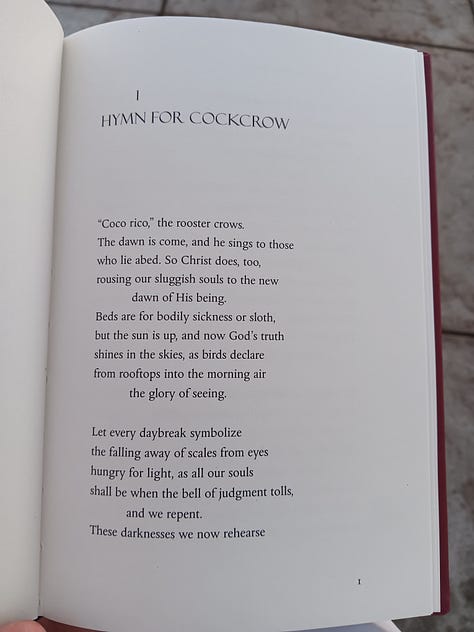

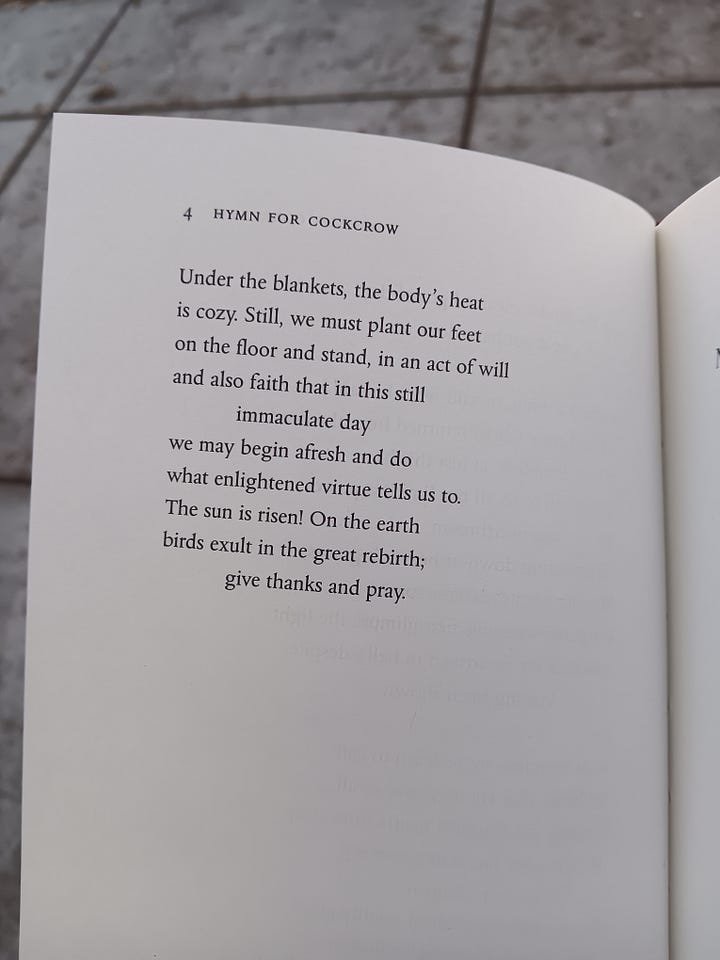

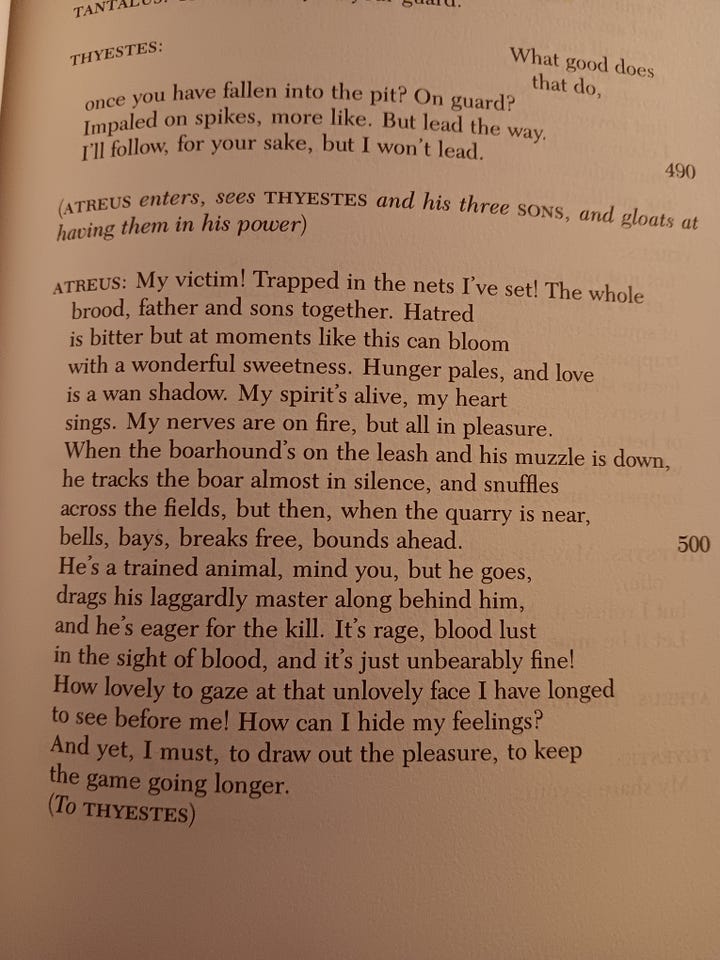

All of these traits, sympathy for his subjects, advocacy for the overlooked or maligned, and a beautiful yet easily readable style, I have found in every subsequent work of translation of his I’ve read. Whether it’s presenting the gritty, raw, and highly embellished character of Seneca’s classical tragedies, the homey piety of Prudentius’ Christian prayers, or highlighting the beautiful fragments of Statius and Claudian’s epic poetry, I’ve continually been encouraged to discover authors and works which I had previously been dissuaded from by harsh, 19th century critics, or which I had never even known to exist.

I’m left with gratitude to this poet and humanist, in spite of differences in faith and politics, and I hope to continue exploring his works. I’m a little sad that I’ve come to really appreciate and engage with his works too late to have written him and gotten, perhaps, to know him or express my delight and gratitude.

Above all, beyond simply expressing that gratitude and heartily recommending his work to others, I want to highlight those virtues I’ve mentioned repeatedly already. I want to emulate, and encourage emulation, of engaging passionately and with loving appreciation with those things worthy of attention. I want to emulate, and encourage emulation of, his breadth of reading, education, and culture. I want to emulate, and encourage emulation of, his sensitivity to a popular, common audience without sacrificing depth or beauty. He had a gift for finding beautiful things, making them accessible, and encouraging the advocacy for the beautiful and overlooked, not least by making known his own love and bringing out the qualities he appreciated in his translations.

I’ll probably continue reading Slavitt’s work, perhaps even venturing to some of his own original poetry, and I can certainly recommend his Latin translations. I’ll close with a characteristic quote he provides in the introduction of his thoroughly enjoyable translation of the hymns in Prudentius’ Kathemerinon,

“Prudentius’s Latin is decorative and his poetic stance is enormously appealing. I have tried to do the voice and suggest to others something of what I admire in it. If I read these poems as objets d’art, I have no objection to my Christian friends reading them another way, as devotions. Indeed, I cannot for the life of me guess which of us will be getting more out of them. The particular belief is perhaps not so much the crucial issue as the yearning for belief- for the faithful feel, in the momentary flaggings of their faith, a fervent longing most agnostics have experienced, whether they admit it or not.”